1. Introduction and problem definition

When I came to Taiwan for the first time, I got the impression that it is a “developed” country: everybody has a car and a mobile phone, factories and companies all along the highways, a high speed railway, one of the tallest skyscrapers of the world in the center of the capital Taipei, and many more hints. Upon a closer look, though, especially as a resident of Taiwan calling it “my home”, it seems to me that the Taiwanese society is in several ways underdeveloped and primitive. Taiwan has huge social problems, with people having low education, low understanding for social interaction and a lack of ethical and moral behaviour. I could give hundreds of examples that support this thesis, for example business fraud, food scandals, low mass media quality, betel nut consumption, extreme religious superstition, etc. However, the longer I stayed in Taiwan the more I felt unhappy about “complaining” and criticising the Taiwanese people. After all, Taiwanese are not “bad people”, and looking down upon them is arrogant and wrong. In order to find a way to “harmonise” my view at Taiwan I consulted the areas of life that help me the most in many cases: science and philosophy. I tried to figure out a way to explain the specific situation of Taiwan and its citizen so that I can understand the people’s behaviour and mentality (and – by this – be able to forgive them). This is the realm of social sciences, psychology and a bit of philosophy. I’d like to illustrate my logic by the topic “traffic”. This is the “public sphere” with the highest impact on everybody’s daily life. Moreover, it is very obvious that Taiwan has a “traffic problem”. Let me circumstantiate this claim with some numbers: Taiwan has a traffic death index of over 35 according to independent statistics (the government officially published a value of 16, but experts say it is definitely not correct). That means, out of 100,000 “traffic acts” (a journey from A to B) 35 never reach their destination (for comparison: Germany 2.8; USA 5.3; Kongo 11.2; Philippines 17). Unfortunately, I lost the link to the source of these values, but as soon as I find it again, I add it here. Some Taiwanese claim that Taiwan is just too small and too many people want to use the little space. I don’t agree to that! Cities like Seoul or Tokyo have a much higher density of people and vehicles and yet the traffic is not that terrible. I see the source of all problems in the individual behaviour and its underlying mentality, and that’s why I want to focus on that in the following descriptions. I will first present my observations on Taiwanese roads, illustrated in graphical sketches. Then I will present a model based on constructive realism that helps identifying the mismatch between “Western” technology (and its usage) and “Taiwanese” mentality and worldview.

It is very important to point out that the following text uses “generalisation” as a tool. Of course, not everybody is the same. Of course, it is not right to blame “everybody” for the flaws of some. If you are Taiwanese and feel offended because you don’t drive like I describe, well, then just don’t feel adressed and be proud of being not like the stereotype depicted here! Unfortunately, Taiwan is not a “feedback culture”. Direct open criticism of others’ behaviour is very seldom and not appreciated. This makes change and progress very slow, because people usually don’t have the trigger to re-think and reflect their behaviour and, therefore, won’t consider changing a custom or habit. I am not in the position to tell Taiwanese what they “should do better”, but if my article makes only one scooter driver hesitate before driving on the sidewalk in the wrong direction through a crowd at a bus stop, I call it “successful”. All these traffic-related death cases are avoidable! But the change to the better can only be achieved when people are open-minded enough to see the real reasons for the problem and the own role in it instead of blaming outer circumstances like the size of the Island or the government.

2. Observations

To explain my observations of traffic behaviour I made illustrations comparing Taiwanese customs (on the right) to an “ideal” (and, by the way, legally demanded) behaviour (on the left). In an original version I labelled the left part with a German flag since I believe the German traffic behaviour is highly regulated and people are used to stick to the rules (except speed limits, to some extend). In order to avoid unnecessary discussions about the correctness of my perception of German traffic, I just label the left side as “ideal case”.

I start with a rather symbolic example: How to deal with a dead-end road. Probably (and hopefully) it doesn’t happen too often in Taiwan, but it does happen, which can be taken as a perfect example of the mindset that most Taiwanese have. This gives a hint of the reasons why the situation here is what it is.

When a road is labelled as a dead end road it would be wise not to drive into it when the destination is not in that road. If it is somewhere “behind” it, one would take another way even if that is longer. Many Taiwanese will enter the road with the “dead end” sign even though they know the destination is beyond the end of the road. This has several reasons. First of all, the trust in road signs is very low, rooted in the low trust in the government and official institutions. Maybe the sign is old and not valid anymore but nobody removed it. Maybe the sign was already invalid in the first place and there is no dead end at all. Maybe someone put the sign there to fool the drivers or just to force them to go another way, but actually the road is open. There is also a considerable amount of drivers in Taiwan that just don’t see the sign. “Road blindness” is a widespread and dangerous phenomenon in Taiwan: People not even recognising what the situation is and what proper action needs to be applied. Another aspect is the high degree of superstition and the strong influence of religious believes: Taiwanese people strongly believe in ideas of “fortune” and “luck”. By praying to various Gods and other heavenly entities in temples and shrines, and by burning incences and huge amounts of Ghost money at home, at shops or at sacred sites, they increase their chances to experience fortunate incidents and to simply have more luck by being favoured by ghosts and gods. By driving into the dead-end road they try this luck. In an environment where nothing, especially not the government, is trustworthy, everything – especially the personal achievement – is based on luck. Why not also a road that might miraculously open up somehow? You never know!

Whereas the former illustration is to depict the mindset of Taiwanese drivers, the next is the hard reality: Queueing at a junction at red traffic lights:

People are expected to line up behind the white mark, independent from the type of vehicle. It is valid for cars, busses, trucks, but also motorcycles and scooters. Bicycles may pass on the right side if there is enough space. The pedestrian crossing has to be kept free in any case, that’s why a white line indicates where to stop. Taiwanese widely ignore the marks on the street completely! And I mean COMPLETELY! Not only they stop on the pedestrian crossings, they also don’t queue in the lanes that are marked, they just squeeze into every available space. Many scooters even overtake the whole queue on the opposite lane and stop in front of it, which – when many scooters do that – jams the junction completely. In many Taiwanese cities the roads, even big ones, have no sidewalk. Pedestrians walk literally on the street and have to fight their way through this chaos. On top of this, many scooters (in the illustration marked in red) even drive in the wrong direction (or, if you want to put it that way, on the wrong side of the street). I’d like to remark that the different number of vehicles in the graphic is just an illusion. On the left side, the queue is just longer. The Taiwanese all drive as far as possible to the front so that the density of vehicles per space is higher. This also slows down the traffic massively!

The next illustration is about parking the car:

When visiting a store, a restaurant, a bank, a market stand or street vendor, Taiwanese usually park their vehicle right in front of it. Doing this with scooters and motorcycles is bad enough, because they block the sidewalk (or side of the road when there is no sidewalk) for pedestrians and especially those with wheelchairs or baby strollers. With cars and those small blue trucks that are ubiquitous in Taiwan it is worse, especially at junctions where they block the pedestrian crossings and make it impossible for busses to turn. Combine this illustration with the previous one, and you can get an idea of the chaos at many junctions here! It is also very common that bus stops are jammed with parked cars and scooters. It is not that there are no parking lots in Taiwan. But Taiwanese prefer the “convenient” way to just exit the car and enter the shop without walking too far. Also, they save the parking fee.

Talking of bus stops, there is another thing that annoys me a lot! Not to say, I am really upset, because this behaviour is the most stupid and dangerous of all: Overtaking a bus at a bus stop on the right side!

In Taichung most roads have no sidewalk. Therefore, bus stops are literally just marks on the road. But this can never excuse the behaviour of many scooter drivers and sometimes even cars that overtake the bus on the right side while it is stopping at a bus stop and passengers enter and exit the bus. Some scooter drivers even honk their horns and drive full speed through the crowd. To complete this: also here I observed scooters doing this from the other side, riding in the wrong direction. This is horribly dangerous for the bus passengers, of course. The same reckless custom happens on the left side of the bus: disregarding the oncoming traffic people try to pass by the bus, sometimes jamming the road or, at least, putting themselves into a very dangerous situation when the space between bus and oncoming car is barely enough for a scooter. The option of waiting patiently behind the bus is seldomly taken into consideration. I take the bus from my home to my workplace every morning and back in the evening. It is a one-hour-ride through the city with 38 bus stops. Once I counted all scooters that pass by the bus on the right side at bus stops, it was 118. Not all of them cause a dangerous situation and might even watch out for pedestrians. But many times it almost comes to a crash with someone exiting the bus. Other crashs are only avoided by the passengers watching out and waiting for the scooters to pass which prolongues the time that the bus stands there with open doors, forcing more traffic participants to wait.

Another Kamikaze manoeuvre that can be observed everywhere and at any time is the way people turn left at junctions. The rule – which is reasonable and useful – is that anyone turning left has to let oncoming traffic pass by first, including the pedestrians on the crossing! Many Taiwanese car drivers ignore this rule and turn left whenever possible AND even when it is impossible. They slowly roll forward more and more until an oncoming vehicle leaves a little too much space or has to stop. Then they quickly rush to the left. Following left-turners only wait for that moment and all rush after the first car, so that the oncoming traffic has to stop completely. Some cars or trucks change to the left lane even long before the junction and drive the last meters before turning on the pedestrian crossing on the left. Scooters are even worse. The common pathway of a left-turning scooter is illustrated here:

Not only the city traffic is an adventure, also a ride on the highway is! Even though the average speed on the expressways is much slower than in Germany, it is not safer or less challenging to use it in Taiwan. The rules for driving on the highway, like overtaking only on the left side, riding “as right as possible”, never using the emergency lane, etc., are – no surprise – widely ignored. Most highways and freeways in Taiwan have three lanes. The idea is that slower vehicles (trucks, slow cars or “relaxed” drivers) take the right lane at 90-100 km/h, the middle lane is for medium speed (110-120 km/h) and the left lane for overtaking at higher speed (>140 km/h). Vehicles should change the lane as seldom as possible and only to the left for overtaking and then back to the “rightest” lane according to their chosen speed. The acceleration lane at the highway entrance is for aligning to the speed on the right lane in order to filter in between two vehicles. Not so in Taiwan:

The blatant impatience that we observed in the city traffic before is also ubiquitous on the highways: People just can’t wait. Slower vehicles are overtaken on both sides, including the emergency lane that is regarded as a fourth lane. When entering the highway, many drivers try to filter in by all means IN FRONT OF that truck! Slow cars often don’t change to the right lane, forcing faster travellers to overtake in risky manoeuvres. Other drivers change lanes out of a sudden without any obvious reason. This causes a high level of unpredictability. You never know what the driver in front of you will do next. What is not obvious from this illustration but not less dangerous: The distance between cars is usually way too short. The rule of thumb is: Your speed in km/h should be the distance in meters to the vehicle ahead of you. Sometimes drivers here leave much too little space (this is also a problem in Germany, I admit).

These observations allow certain conclusions: Obviously, Taiwanese people are extremely impatient, self-centered, reckless and unaware of the effect of their actions and decisions. No need to mention that this driving style causes conflicts and risks. However, it is also my observation that Taiwanese usually are not very upset about other drivers. From personal conversations I know that most Taiwanese don’t like the local traffic and they criticise other drivers a lot. But on the road, people usually don’t complain or insist on their rights. Misconduct is accepted and ignored. What would cause a massive case of “road rage” and aggression in Germany is so common in Taiwan that nobody really bothers.

3. Interpretation

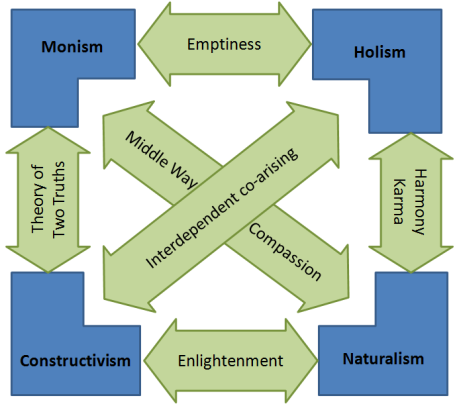

“Traffic” as a public domain based on the development of the automobile technology is a “Western” invention. Carl Benz (who built the first motorised vehicle), Henry Ford (who initiated mass production of cars), Rudolf Diesel (who invented an alternative engine that uses lighter fuel) – the pioneers of automobiles are all European or American. Its development is highly embedded into “Western” social and cultural constitutions. During the colonisation by the West in the past century, especially by US-American geopolitical investment in East Asia (Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam) after World War II, Confucian societies were confronted with Western approaches of life conduct such as capitalism and democracy, as well as with Western technologies like automobiles. However, these domains were “uprooted” from their original cultural soil in which they were in line with values, worldviews and social contracts, and imposed onto societies with completely different preconditions, mentalities and education levels. In order to understand this aspect better, the concept of “constructive realism”, suggested by Fritz Wallner ([1],[2]) can be applied.

Constructive Realism distinguishes three levels of reality. The first, most fundamental, is the “actuality” (German: Wirklichkeit). It is the real world that we find ourselves in, that all living creatures must rely on to survive. It may have certain structures or may function according to certain rules, but humans have no access to these structures or rules, and no way to recognise them. No matter how hard we attempt to explain these structures, it will always be incomplete or insufficient, because we are limited in our cognitive tools. Therefore, the explanations and their comprehensions remain a human construction. The structures of this world, its temporal and spatial distances and causal laws, are all hypotheses proposed by mankind. For our purpose, we don’t need to speculate about this level of reality, but leave it to the philosophers. We are more interested in the other two levels that constitute the world that we are able to understand: our lifeworld and several microworlds (in analogy to Berger and Luckmann ([9]) who named them “social everyday reality” and “provinces of meaning” or “subuniverses”, respectively). The knowledge created within each construction results in different worldviews with distinct functions, manifested and sustained by different types of language.

The lifeworld is the reality sphere in which an individual find itself living in. The contents of it can neither be exhausted nor can human beings go beyond their boundaries. Lifeworlds exist inevitably at a particular point in history, differing by historical age and culture, undergoing slow or drastic changes. However, despite the changes, lifeworlds are constantly sustained by a transcendental formal structure called cultural heritage. The perception and realisation (or better: construction) of the lifeworld by a cultural group (i.e. a society, the citizen of a nation, etc.) can be characterised by originative thinking (according to Heidegger [3], [4]), substantive rationality (as in Weber 1921/1963 [5]) and participative construction (see Levi-Bruhl [7]). The constitution of the lifeworld helps the members of the cultural group to form worldviews concerning the “common” metaphysical questions of life, like purpose and meaning of life, self-cultivation and self-recognition, or value and belief-systems (Whorf [10]).

The other world construction is that of the microworld. Microworlds are the realm of “experts” and people with specifically elaborated knowledge in particular fields such as natural or social and normative sciences, politics, economy, etc. Within any given microworld the reality of the given world is replaced by a second order constructed reality that can be verified by empirical methods. The knowledge created in a microworld is characterised by technical thinking (in terms of Heidegger), a formal rationality (Weber [5], [6]) and dominative construction (Evans-Pritchard [8]). Microworlds impact our worldviews by facilitating the recognition and understanding of the “real” world (see, for example, Kuhn [11]).

It is worthwhile to have a closer look at the ambivalent influence that lifeworld and microworlds have on each other. The most important carrier of culture is language. It is also the medium through which lifeworlds are comprehended, analysed and recorded (see, for example, Wittgenstein’s “language game” approach, [13]). People sharing a cultural heritage also share the power of reinterpreting it. Intersubjective communication may determine the interpretation of cultural tradition and helps to establish acceptable standards of behaviour, identify with their community, and strengthen social integration. The language sets of lifeworlds and specific microworlds are fundamentally different in function and character and, therefore, incompatible. Yet, the development of scientific and other microworlds has massive impact onto the lifeworld of the social and cultural realms that they affect. According to Habermas’ theory of the differentiation of social systems from peoples’ lifeworlds,[14] the progress of microworlds that gain enough power and impact to constitute a “social system” can lead to a discrepancy or even a mismatch between the lifeworld of people and one or more microworlds that they are confronted with. The original functions of communication (satisfying three social needs: cultural reproduction, social integration, individual socialisation) are undermined and substituted by material reproduction, social control and individual autonomy. In a process Habermas called “colonisation of the lifeworld by the system” the originative thinking is replaced by technical thinking, so that money and power replace the position of language in the lifeworld, becoming the media for system integration. Systems in the lifeworld are liberated from regulation by social norms and become more and more autonomous. Finally, the new order of the social system begins to instrumentalise the lifeworld. In simpler words: Individual people embedded into a certain lifeworld (a culture, a society) gain specific knowledge to elaborate a microworld (for example: a new technology, a new physical law, a new political theory, a new jurisdiction paradigm, a new education or psychotherapy approach). When this microworld grows big enough it has a recurrent effect onto the lifeworld it is affecting. In case it is the lifeworld of the society it originates from, it may or may not be in harmony with the lifeworld’s consequences on worldview (the meaning of life, values, virtues, etc.). When it matches there is no conflict, when it doesn’t match the lifeworld and microworld challenge each other and are forced to refine and re-define their worldviews. When the affected lifeworld is that of a completely different cultural or social realm, the impact might cause drastic changes and disharmonies in both lifeworld and microworld. An example might be the social system (and form of “microworld”) “capitalism”. Max Weber identified its roots dating back to Protestant Ethics and its Zeitgeist of Europe in the 16th/17th century. It emerged and gained power because the lifeworld of European societies at that time was “right” for it. The values, virtues and beliefs of the people shaped the principles and political and economic implementation of “capitalism” in its development during the 19th and early 20th century. When it was “exported” to other parts of the world, especially East Asia (Japan, Korea, China, Taiwan) around the mid of the last century, it was imposed onto Confucian, non-individualistic societies. In other words: The microworld “capitalism” that flourished on the soil of the lifeworld “Christian, individualistic, Kantian, democratic” was uprooted and transplanted onto a lifeworld “Taoist, interrelational, Confucian” (the political organisation was too different for the mentioned countries to be termed here). The technical system was exported without the normative guidelines, without the instructions. Today we see an extremely unhealthy, greedy, exorbitant materialistic form of hyper-capitalism in East Asian countries, going along with high degree of stress-related depression, high suicide rates and rampant unhappiness and psychological degeneration, not to speak of massive environmental destruction.

Social psychologist Kuang-Kuo Hwang from National Taiwan University applied this model to “indigenous Psychology”,[15] I exploited it to reason my approach of elaborating an “Asian” concept of “Applied Ethics” based on Confucian, Buddhist and Taoist philosophy. I believe that it can also be applied perfectly to “traffic”: After the invention of the technology “automobile” it entered the public domain through mass production and the construction of infrastructure (roads, gas stations, parking lots, etc.) and the economic market. It was accompanied over decades by governance and regulation that is based on European understandings of “law and order”, individual rights, safety, etc. “Individual” traffic in which a technical layman (someone who doesn’t know how a car works) is given the control over a technical artefact (a car) that is so strong that it can cause damage and death when used improperly requires people with a certain degree of social and ethical mentality. In post-enlightenment era (and post-WWII) Europe this was given. An individualistic democratic society in which everyone receives education in technical and normative aspects of life, learning about cause-effect-relations, physics, but also social and moral behaviour, an adult can be considered “prepared to participate in automobile traffic”. A certain degree of patience, respect, consideration and awareness of a “social contract” are preconditions for “traffic” in this form.

What happened in Taiwan? Until the 1980s wide parts of the population were too poor to own a car. After the democratisation processes and growing wealth of the population, the roads (that were mostly in poor conditions) filled rapidly with cars and small trucks. The traffic death rate was tremendously high because people drove the cars and trucks just like they drove scooters or bicycles before. Most people, especially the elderly, never received a proper school education, have no sense for speed and physical energy transformation, and additionally show a lack of patience, caution and other necessary character dispositions. Young people are not encouraged to drive “better” because there are no incentives for it and – a phenomenon of a Confucian society – nobody tells them to or criticises them. The school and education system is designed to prepare the Kids for a life dominated by technical and practical skills (more Western microworlds: microelectronic industry, capitalist economy, universities, functionally differentiated society, etc.), but doesn’t make them “free thinkers” with high personal moral integrity. Moreover, except making it obligatory to wear helmets on motorcycles and scooters, there is no significant political attempt to improve the traffic situation (for example by pushing through parking regulations, speed limits, etc., or by controlling the traffic with a higher presence of policemen, or by improving the driver education and license tests). With other words: the social, historical and cultural preconditions for the microworld “traffic” in Taiwan are fundamentally different from those in Europe.

4. Conclusion

What is the conclusion from such a finding? Criticism is only “constructive” (and criticism should always be constructive, otherwise it is just a complaint) when an alternative or strategy for improvement is suggested or offered. However, the case here is not so simple. The problem can be expressed in two ways: “Taiwanese are not ready for individual motorised traffic.” or “Individual motorised traffic is not suitable for the Taiwanese society.”. The difference is the point of intervention: Either something has to be changed in the microworld “traffic” or its implementation in the society, or the society has to re-think and refine its conclusions from lifeworld aspects, that means its values and worldviews and, as a consequence, its actual behaviour and life conduct. The question is: What is more difficult? It will certainly be impossible to “remove” the microworld “traffic” from this Island. It has conveniences that nobody wants to miss and became a substantial part of daily life. However, the regulations and guidelines that tell how “traffic” is done are not natural laws or eternally fixed. They can and should be adapted for the needs and specificities of the particular society they are subjected on. Another solution could be to design the infrastructure of roads and other traffic-related facilities in a way that “forces” drivers to drive slower or more carefully (for example: build proper sidewalks with “bus stop bays”, construct separating elements between lanes, make roads so narrow that overtaking becomes impossible, etc.). Maybe a higher presence of policemen and higher penalties would do, or more strict driver education. Ultimately, given the latest developments in autonomous cars and self-driving vehicles, it could be a great solution for Taiwan to take the responsibility out of Taiwanese drivers’ hands and let the cars “decide” about speed, distance and manoeuvres. These are technical questions about the fashion of the microworld, most of which are political aspects.

However, all these solutions sound a little bit like “We accept that Taiwanese are not mentally capable of western-style traffic, so we make it “idiot-proof” in order to keep it running.”. What about the other option of “changing peoples’ mindsets”? Is it possible to “make a society more patient” or to “create an environment of safety and care” in which people reflect selflessly what they are doing and how it affects others? From a certain perspective it is much harder to change habits and behaviour patterns than laws and regulations. I believe, however, that the most sustainable solution is a mix of both. As long as Taiwanese don’t start reflecting and questioning their normative foundations, their ethics and morals, and the way they choose to live together and cooperate, the best political, legal or technological solution won’t bring groundbreaking benefits. Siddharta Gautama Buddha taught (and I agree fully) that the mind creates thoughts, thoughts become action, actions become habits, habits become character (or “personality”) and character determines the “fate” of a person. It all starts with the mindset: The starting point of all individual and interrelational change is the awareness for the phenomena and characteristics of this world. Raising awareness and supporting the mindfulness of people can partly be achieved by institutionalised education (Kindergarten, schools, etc.), but is mostly a matter of “social environment”. Young people can be “taught” how to “do right” in traffic, but the more sustainable way would be to equip them with a mindset that tells them “I should be patient in this situation because otherwise I cause trouble to another traffic participant!” or “The safety of that pedestrian is more important than me arriving in time!”, rather than “I am patient because I was told to be.” or “I drive slowly because otherwise the policeman will give me a penalty.”. A traditionalist might insist on Confucian values and social models, for example favour (renqing), relationships (guanxi) and face (mientse). From this, a theory of distributive justice as basic part of ordinary people’s ethics can be deducted.[16] However, it turned out that “Confucian traffic conduct” obviously doesn’t work out well. To a certain extend, people might have to give up their idea of “face” and start giving each other feedback and criticism in order to induce a change to the better. Maybe people should stop understanding “burning ghost money” and “bowing with incenses in front of a Buddha statue” as Buddhist or Taoist practice, but spend more efforts and time on practicing mindfulness and awareness in order to manifest character dispositions such as patience, empathy and compassion (which would truly be “the Buddhist way”). Maybe people should be motivated (by school education, mass media, etc.) to reflect upon the question of “how we want to live” in this society and on ways to personally contribute to the “change to the better”. Changes like this usually need several decades, at least one or two generations. When more and more (young?) people raise their voices against careless and reckless driving, more and more people might feel urged to re-think their behaviour. How many traffic death cases have to happen before enough people change their driving style? I see Taiwan on the way, but there is still a long distance to go when the pace is not massively accelerated. And, from my point of view, this is only possible by reflecting on worldview and value systems as part of the lifeworld. Blaming or working on the microworld “traffic” alone will not solve the problem.

-

Wallner FG, “Constructive Realism: Aspects of a New Epistemological Movement”, Braumüller Pub., Vienna, Austria, 1994

-

Wallner FG, “The Movement of Constructive Realism”, Braumüller Pub., Vienna, Austria, 1997

-

Heidegger M, “Discourse on thinking”, Harper and Row, New York, USA, 1966

-

Heidegger M, “The Principle of Ground”, in: Man and World (ed. T. Hoeller), pp.207-222, 1974

-

Weber M, “The Sociology of Religion”, Beacon Press, Boston, USA, 1921/1963

-

Weber M, “The Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism”, Routledge, London, UK, 1930/1992

-

Levy-Bruhl L, “How Natives Think”, Washington Square Press, New York, USA, 1910/1966

-

Evans-Pritchard EE, “Social Anthropology and other essays”, Free Press, New York, USA, 1964

-

Berger PL, Luckmann T, “The Social Construction of Reality”, Anchor Books, New York, USA, 1966.

-

Whorf BL, “Science and Linguistics”, in: Language, Thought and Reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf (ed. JB Carroll), pp.207-219, MIT Press, Cambridge, USA, 1956

-

Kuhn T, “Possible Worlds in the History of Science”, in: Possible worlds in humanities, arts and sciences, proceedings of Nobel Symposium 65 (ed. S Allen), pp.9-32, deGruyter, New York, USA, 1986

-

Kuhn T, “What are scientific revolutions?”, in: The Probabilistic Revolution (eds. L Kruger, LJ Datson, M Heidelberger), pp.7-22, MIT Press, Cambridge, USA, 1987

-

Wittgenstein L, “Philosophical investigations”, Blackwell, Oxford, UK, 1945/1958

-

Habermas J, “Theory of Communicative Action (Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason, Vol.II)”, Beacon Press, Boston, USA, 1978

-

Hwang KK, “Foundations of Chinese Psychology – Confucian Social Relations”, Springer, New York, USA, 2012

-

Hwang KK, “The deep structure of Confucianism: a social psychological approach”, Asian Philosophy 2001, 11(3), pp.179